Why A.I. Makes Surveillance Exponentially More Powerful

News flash: no human monitor is necessary in order for surveillance programs to understand a person’s text messages in the truest sense of the word!

October 07, 2015

In 2013, Edward Snowden leaked a number of classified intelligence documents, revealing a series of shockingly rigorous surveillance programs being administered by the US intelligence community. First, Snowden showed that the NSA had ordered Verizon to hand over consumer call information on a daily basis, including the time, location and duration of calls made across the country, as well as the names of the call senders and receivers. His leaks further demonstrated that, through a unique and especially productive relationship with AT&T, the NSA had been able to spy on vast quantities of Internet traffic data as it flowed across the company’s domestic networks. Snowden’s actions sparked a period of great controversy across our country that is still not resolved. Apple continues to fight the intelligence community to retain the right to encrypt iPhone users’ text messages, intent on demonstrating that the company is trying to protect customer information. At the same time, Homeland Security has been shutting down nodes of Tor, the infamous proxy server network, in an attempt to make it more difficult for Internet users to remain anonymous.

Despite the government’s clear breaches of our commonly held conceptions of privacy, only a surprisingly few Americans feel threatened by surveillance programs. There exists a popular notion that, regardless of its data access sources, the intelligence community cannot possibly have the time and personnel required to monitor every individual’s communications. South Park, a TV comedy satire, aired an episode entitled “Let Go, Let Gov” which ridicules the idea that the NSA could possibly have enough people to monitor the calls, texts and emails of all American citizens.

It is easy to find comfort in this mentality. So what if machines can scan through the massive corpus of text and audio communications of ordinary people? As long as these machines do not UNDERSTAND what is being said, then our privacy has not been invaded—right? It’s true that surveillance programs might be able to find keywords of interest quite easily. Maybe they can pinpoint, with efficiency, individuals who are using words like “cocaine” or “kilo” on a given day. Maybe they can efficiently pinpoint individuals who have looked into the construction of bombs, and ways to obtain AK-47s. The average American does not care about these capabilities, because average Americans are not felons. What we do care about is that our personal lives are not constantly being poked through and our actions continually analyzed; if this were the case, then our freedoms would be inhibited by a cloud of anxiety. Privacy, to many, is one of the most precious liberties.

So, while the public seems concerned about individual privacy on the surface, it doesn’t seem to care enough to figure out what an impedance of this privacy would require. News flash: no human being is necessary in order for surveillance programs to understand a person’s text messages in the truest sense of the word! This becomes more obvious with every advancement in Artificial Intelligence technology.

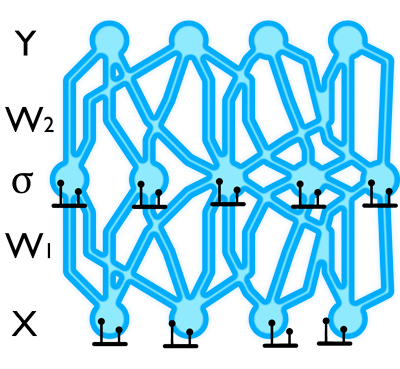

What enables A.I. programs to “understand?” Just think about Siri, Cortana, or Google Now, personal assistant systems that have two main technological components. The first is speech recognition, used to convert audio waves into text. The second is language inference, which takes segments of text and infers about its meaning. It is the latter component that inspires true awe. Recent breakthroughs in natural language processing have brought a revolution to the field.

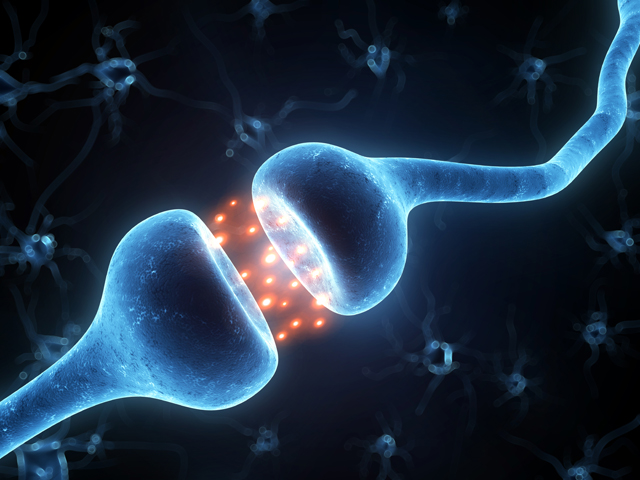

Computers are now able to process time-ordered sequences of language by coupling neural network models with external memory resources that preserve information over time. The resulting system is a computer that mimics the short-term memory of a human brain. It turns out that humans don’t start thinking from scratch every second; as you read this post, you understand each word in conjunction with your understanding of the previous words. Your thoughts persist, and this persistence allows you to learn time-based dependencies as you develop your language skills.

In the same sense, thought persistence affords A.I. systems the ability to learn time-based dependencies when presented with massive corpuses of language examples. Similar models are also employed to learn time dependencies within sequences of network traffic. In the same way you would consider each word to be a piece along the timeline of a sentence when inferring about that sentence’s meaning, you can consider every internet action taken by a given user to be a piece along the timeline of his browsing session when inferring about his thoughts and intentions. Learning from significant quantities of examples, these systems are able to perform critical analyses upon new text communications, as well as upon new sequences of network browsing data.

It is not my intention to make a statement about what surveillance programs are doing; I do not have this knowledge, nor do I wish it to appear that I do. My purpose is simply to point out what these programs could be doing given the information they have access to and the emergence of tremendously capable new A.I. systems. The majority of these systems are developed at U.S. universities and sponsored by government agencies including NSF, DARPA and a select number of others. It is worth taking a moment every time and again to consider the implications of A.I. developments, given the rapid progression of this field and the number of information access points held by certain large establishments.