DeepMind’s Subtle Revolution

DeepMind’s Atari agent learns to play video games in the same way that infant mammals learn to perform various functions.

August 17, 2015

Last summer, Google purchased a London-based A.I. startup called DeepMind Technologies for just over $500 million, placing an astounding bet on a dozen artificial intelligence researchers. At the time, these individuals were working on what would become one of the greatest A.I. achievements to date. Researchers at DeepMind set out the ambitious goal of building a computer brain that could learn to play a variety of Atari video games using nothing but raw visual data. What this means is that the computer sees exactly what you, the human gamer, would see when playing these Atari games. Beyond this, the computer agent would be fed a negative reward signal when the game is failed, and a positive reward indicative of how well the agent has done when the game is completed successfully. The technology behind this system is fascinating, but how can you understand how it works?

Imagine that you are learning to walk for the very first time. The method you learn by precludes the use of any previous knowledge or experience. What you have is a highly complex machine with many knobs to be tuned that, when adjusted correctly, can determine effectively what signals should be sent to your muscles given the visual inputs it receives from your eyes. In order to tune this machine, you must first fail; at times, you will topple, and a negative reward signal will be propagated through the machine with advice on how to best adjust these knobs. Eventually, after sufficient trial and error, you will achieve a positive reward. This could be the dopamine rush that accompanies reaching your mother’s arms, or finally attaining that alluring teddy bear that was just out of reach. The reward signal will again be propagated through the machine, further updating the parameters that constitute its calculus.

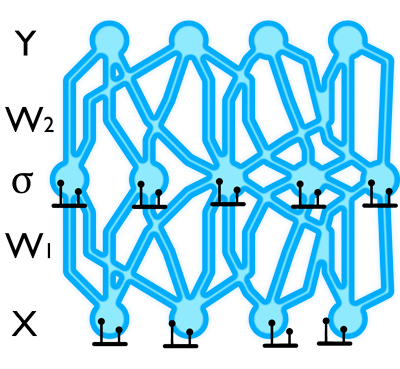

This process should not sound arcane: it is, in fact, the very method postulated to operate in the learning development of mammals. When we train the dog to behave properly in our house, there is a reason that we give it a treat when it has done well and a scolding (or else neutral feedback) when it fails. Inside of the mammalian brain, billions of processing nodes are allotted to form the precise machine of which we speak. These node networks have many parameters (“knobs”) that determine what signals are passed forward in each segment given the inputs that are received. In order for the brain to perform necessary functions, these parameters must be adjusted by means of positive and negative successes.

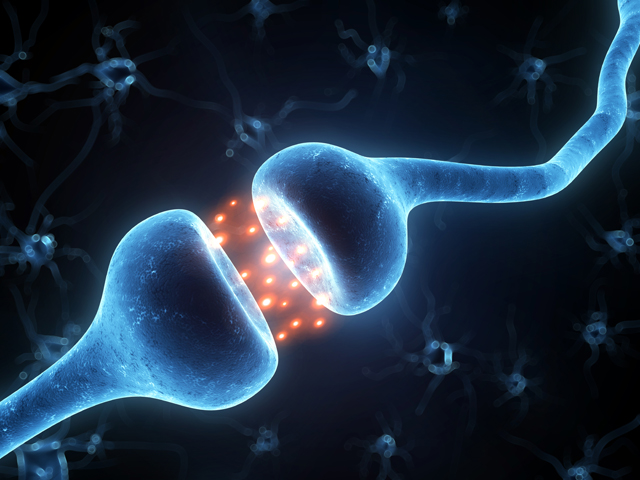

One category of such parameters that has been the focus of great attention in recent science is the synaptic weights. These weights determine how incoming information from previous areas is to be combined at a given neuron in the network, and their filtering mechanisms are believed to play an important role in human cognition. Scientists have sought to build mathematical abstractions that mimic this neural filtering process, using simulated brain cell networks with connection weight values that determine how information is combined and passed forward in each segment.

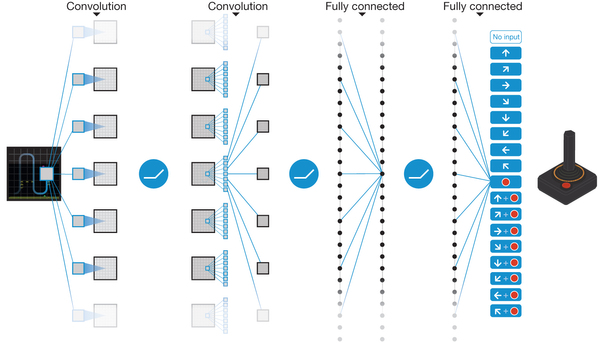

To accomplish the autonomous Atari agent feat, DeepMind researchers made use of one such neural network designed to mimic the processing pipeline of the brain’s visual system as discovered by neurophysiologists David H. Hubel and Torsten Wiesel in the late 1950s and early 60s. The network takes as input a set of pixel values that represent the screen of a given game, and it outputs the game action that it has decided to take given the input visual state. During the learning process, connection weights in the DeepMind network are updated according to the reward signals received by means of a biologically inspired reinforcement learning procedure.

This computer brain, like humans and other mammals, learns via trial and error. Exploring the gaming environment, the agent tries out possible actions at random, adjusting its synaptic weights according to the reward signals that are received. As the agent learns more about the gaming world, it begins to exploit the information that it has gathered, making decisions based on experience in replacement of random choices with increasing frequency. Miraculously, the computer agent is able to achieve a performance level comparable to that of professional human gamers across a set of 49 different Atari games, using the same algorithm and architecture in each case. For each game, a separate agent instance is created, and the agent learns successful policies directly from high-dimensional sensory inputs during 36 hours of training. This generalized artificial intelligence is an absolute breakthrough in the field—an intellectual horsepower that can be harnessed to conquer a diverse range of complex tasks. I believe that we are witnessing one of the first true milestones of A.I. with this project, and that we will be seeing much more of the like in coming years.