Evolution’s Paramount Gift: The Ability to Learn

To solve intelligence, we must solve the learning dynamics of the brain.

July 08, 2016

The human brain is arguably the most advanced and intricate information processing device in existence. Our experience of the world and of ourselves within it is realized entirely within the brain; this is, perhaps, the essence of what it means to be a conscious being. Often in scientific research, we observe and analyze the neural activity patterns of fully-developed primates in order to better understand perception and cognition. By analyzing and modeling the functionalities of an adult brain at a single point in time, however, scientists only scratch the surface of what remains to be uncovered about the beauty of the brain. A separate genus of researchers is placing an emphasis on the learning dynamics of developing brains as they are exposed to various perceptual and cognitive experiences over time. New momentum suggests that learning processes may contain the real meat of what remains to be uncovered about intelligence.

Scientists have demonstrated time and again that the brain’s perception systems are biased by nurture, and that their functionalities are owed in large part to learning dynamics. Neurophysiologists David H. Hubel and Torsten Wiesel broke the surface for our understanding of perceptual development with a study performed on cats. For the experiment, Hubel and Wiesel took a pack of kittens and separated them into two groups: those that would be raised in an environment consisting solely of vertical lines, and those that would be raised in one consisting solely of horizontal lines. Each group was placed in a cage with wallpaper consisting only of black-and-white stripes of their specified orientation for the first several weeks of their lives. Releasing these kittens into the wild after the development period, the duo found that the vertical-world cats were blind to horizontal lines and edges, and vice-versa for the horizontal-world cats. The brains of these cats had dedicated all of their vision neurons to detecting one orientation, and they had neglected the other. The findings were a revelation; when the pair won a Nobel Prize in 1981, the study was cited as a critical factor.

While we tend to think of higher cognitive functioning as independent of sensory perception, the two are closely linked. What would it be like to live in a world where you cannot perceive vertical lines? Does a vertical-world human child undergo a different conscious experience than a horizontal-world human child? The answer is yes, to a greater extent than many believe.

As we develop them, we come to think of our thoughts and ideas as more substantial than perceptual signals. It remains the case, however, that many of these conscious ideas are rooted in perception systems. On the one hand, when we consider the idea “chair,” the whole of the concept has more substance than a picture of a chair can convey. Similarly, the fragrance of a girlfriend or boyfriend has more substance than a set of air particles could possibly hold. These facts notwithstanding, the idea “chair” and the smell of a significant other are inseparable from our perceptions. To think about the concept of a chair without picturing a chair in one’s mind is a difficult task. Similarly, it’s hard to describe the smell of a significant other without replaying that sensory experience in the mind. These perceptions, as scientists have discovered, depend largely upon the history of sensual exposure, and they are owed in great deal to the brain’s learning processes.

To say that all of cognition is perception would be utterly naive. But there is sufficient evidence to suggest that even higher-level cognitive tasks, such as the synthesizing of visual and literary art, rely upon neural infrastructures that are also heavily dependent on nurture. Albert Camus, speculating about why there have only been two ages of great tragic theater, suggested that “great periods of tragic art occur, in history, during centuries of crucial change, at moments when the lives of whole peoples are heavy both with glory and with menace, when the future is uncertain and the present dramatic.” The genius of a great tragedy writer, it would appear, is not owed merely to his or her genetic make-up. The environmental influences of the time play a large role in the development of that genius.

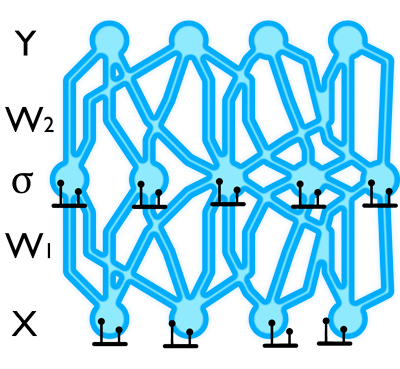

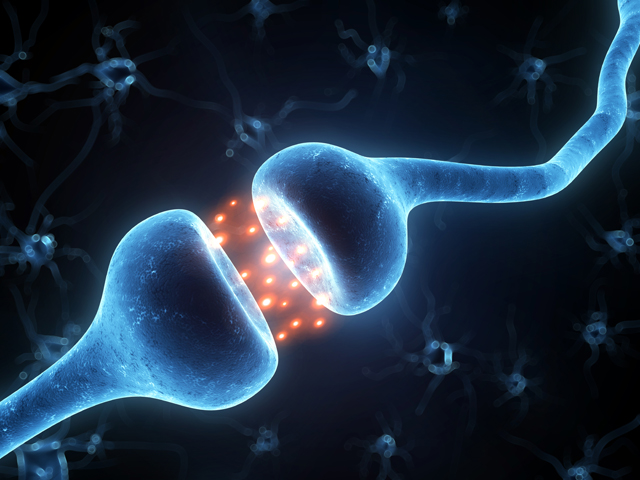

Within the brain’s neural networks, the genome plays a smaller role than many assume. The main job of our genes is to facilitate the transfer function—or the “input-output nonlinearity”—that determines whether a particular neuron should fire an output given a set of input signals. This decision is made inside of the Soma, which contains all of the cell’s genetic information. While these transfer functions are important, a more critical parameter of the brain’s information processing pipeline is synaptic connectivity. The states of the electrochemical junctions between connected neurons, called synapses, determine how a firing signal from the sender neuron is magnified or suppressed before it is passed on to the receiver neuron. The strengths of these synaptic connections change with experience according to a sophisticated learning regime.

The ability to learn via cortical plasticity rules is a critical feature of the brain. If we are to truly understand intelligence, we must understand the learning rules that dictate how cognitive processes arise from experience. What would progress look like if we took the learning-centric paradigm and stretched it along the many orthogonal dimensions of intelligence science?

For one, it might look a lot like the University of Chicago-led study published in Nature Neuroscience last Fall. Authors of the study provide novel evidence in support of a mathematical model that explains how the brain forms persistent neural networks to adapt to what it senses. To acquire the empirical data for this study, David Sheinberg of Brown University measured the changes in activity patterns of neurons in the IT cortex of non-human primates as they observed novel and familiar stimuli. Using Dr. Sheinberg’s data, the Chicago researchers were able to mathematically infer rules about how learning occurs at the synaptic level. These rules confirmed the basic assumptions of a model theorized over 30 years ago by a Nobel Laureate physicist and his colleagues.

Beyond empirical studies on synaptic plasticity, further progress will come with investigations into probabilistic programming techniques. The processing pipelines of the brain are not entirely deterministic; neurons and synapses are inherently random, thanks to a range of different noises. This randomness serves as a resource for computation and learning in the brain, enabling efficient probabilistic inference through sampling. A recent paper published in the journal Science describes a new type of machine learning system that is capable of quickly learning a range of concepts using a probabilistic programming framework.

Most importantly of all, progress will come with an understanding that brain modeling & emulation cannot require an exact simulation of each neuron in the brain down to the quantum level. There will be some level of abstraction involved in the process—abstraction as to those aspects of the biochemistry and physics of the brain that are important in generating our intelligence. When the scientific community comes to an agreement on this, we will have taken a large step forward for our communal understanding.