Knowledge Atoms and Representational Features

Recently, researchers have devised learning algorithms that enable machines to develop high-level knowledge structures.

August 31, 2015

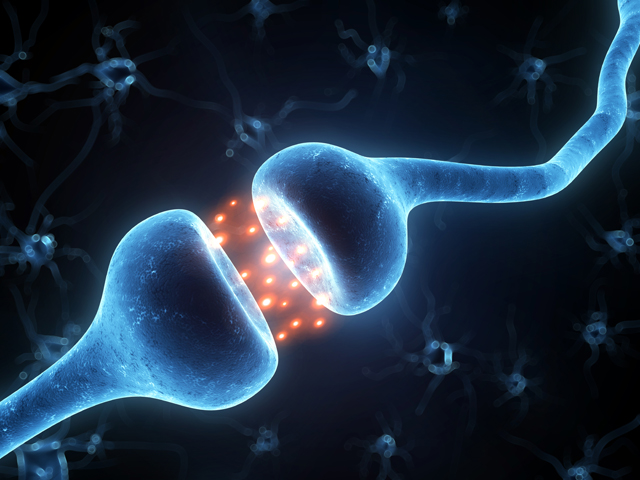

In the mid-1980s, a young cognitive scientist by the name of Paul Smolensky developed a theory of information processing, calling it “Harmony Theory,” to describe human perception using interconnected networks of simple units. Before his time, perception was understood as a task of logic-based reasoning, with researchers following what was known as the symbolic paradigm to describe the processes that lead to intelligent behavior. With Harmony Theory, Smolensky showed how neural activation patterns could be reconciled with conceptual-level symbolic description; a neuron in the human brain, he explained, could be interpreted as a particular type of knowledge structure according to the signal filtering that it performed. Smolensky analyzed the spreading of these activations as an optimization of self-consistency, or “harmony,” a form of statistical inference and a flexible kind of schema-based reasoning. In recent years, machine learning scientists have harnessed this connection-based model of inference, devising learning algorithms for the proposed “Harmonium” (now called a Restricted Boltzmann Machine) that enable machines to develop high-level knowledge structures and effectively summarize the content of data inputs. This whole concept may sound daunting, however, it is relatively easy to understand.

Consider a simple medical experiment. Assume that we have a group of 10000 people, each of which was found to have one of ten particular illnesses of interest. For each subject, we log all of the obtainable data: symptoms, outcomes of tests, the course of illness, etc., as well as the label of the virus that he or she has. From this data, we learn to build an inference model for future cases: take as input the various symptoms that an individual claims to experience, and output a diagnosis for this individual. In classical medicine, a fairly significant amount of hand engineering may go into the construction of this model. For example, if a patient is experiencing stomach cramps and diarrhea, then we might assume that this patient is having stomach issues, and thus “stomach complication” would constitute a higher-level feature of our predictive model. In this sense, stomach complication may be considered a “knowledge atom,” which is either on or off for a given human subject depending on a particular combination of the lower level data that was observed.

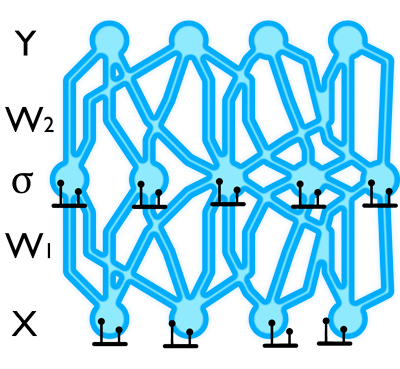

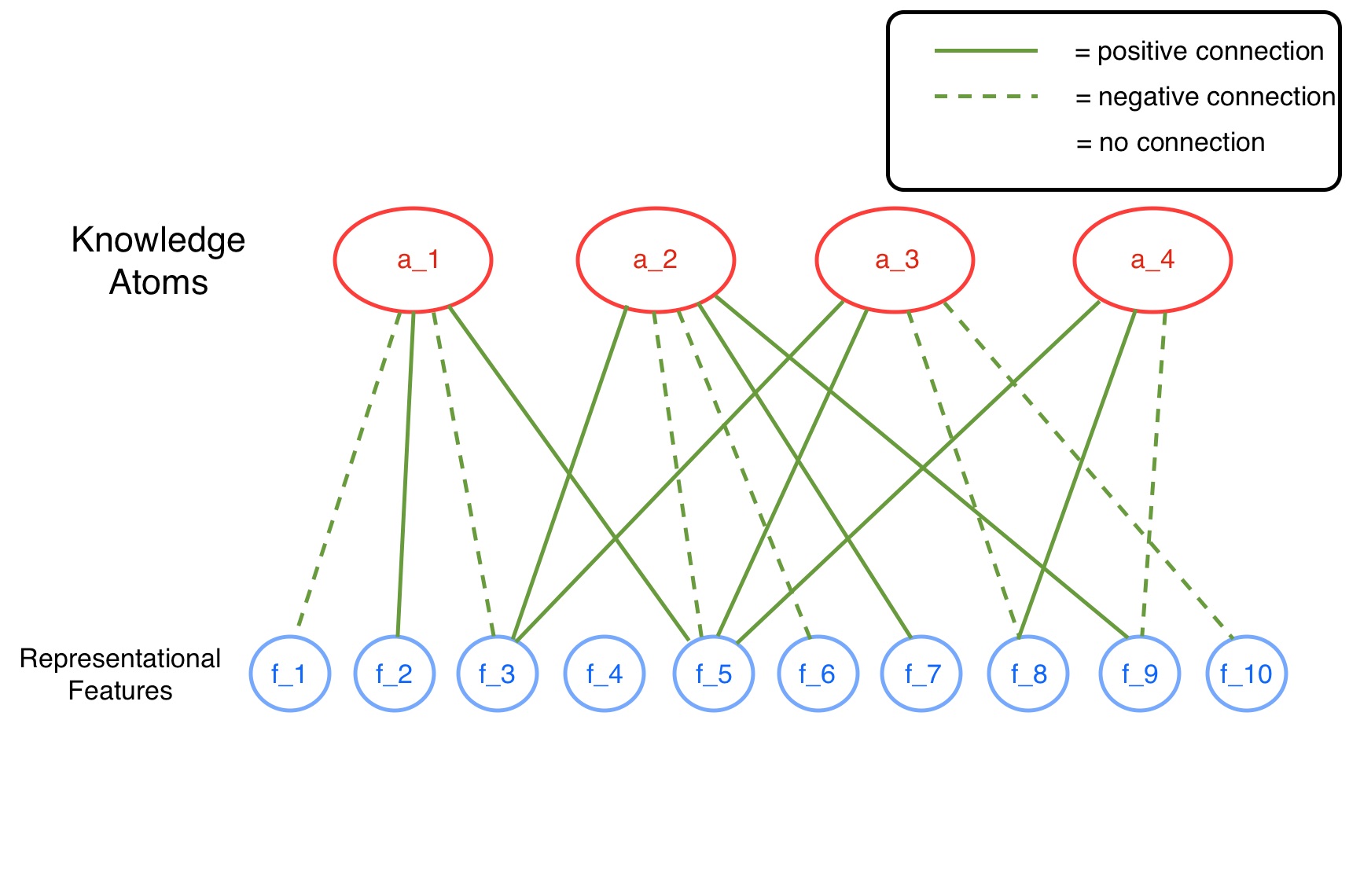

For reference, take a look at the diagram at the top of this page. In the case of the medical experiment, the representational features shown would be symptoms, test results, and all other data attributes collected on our human subjects. The knowledge atoms, such as stomach complication, are represented as weighted combinations of these lower-level features. If the presence of a particular feature does not affect whether or not a given knowledge atom is activated, then the atom will have no connection to that feature. If the presence of a feature contributes positively to the activation of that atom, then a positive connection will exist; further, if a particular feature is inhibitory of a given knowledge atom, then a negative connection will exist. The stomach complication knowledge structure, for example, could be represented by atom a_1 in the diagram above. In this case, stomach cramps and diarrhea would constitute representational features f_2 and f_5, since these attributes are known to indicate the presence of stomach complications. Head pain, on the other hand, might constitute feature f_4, since the presence of this attribute would appear to have no effect on whether or not stomach complications are apparent. Features f_1 and f_3 would be attributes that indicate the absence of stomach complications.

As mentioned, a medical researcher will often handcraft these knowledge structures via an analytical approach, using her medical expertise to determine the effects of every symptom on every knowledge atom. Thus, the human subject data is not used in the development of these high-level knowledge structures. It is only after these structures have been developed that human examples are finally employed: a regression may be performed, for instance, using the data and illness label of each subject to determine the impact of each knowledge atom’s activation on illness classification.

One of the biggest breakthroughs in machine learning came when researchers discovered how to make use of examples for the task of constructing the knowledge atoms themselves. Harnessing Dr. Smolensky’s Harmonium model, these researchers assign probabilities to the various possible knowledge atom configurations according to their self-consistency, or “harmony,” given the data that is observed. Using this probability model, along with state-of-the-art computational statistics methods, researchers are able to find the set of knowledge atoms that maximize the likelihood of the observed data. You can imagine that the knowledge base of a human individual might be a function of the experiential variety to which he or she has been exposed; this is a basic principle of human development. In the same sense, the usefulness of these machine-learned knowledge structures is a function of the variety present in the training examples.

This connection-based inference model can be applied to fields far beyond medicine. The same generalized learning model is used to construct high-level visual attributes from image examples: with pixel brightness values as representational features, machines develop knowledge atoms that detect edges and other types of visual structure by means of the same practices. It is in areas as such, where the input data is analogous to sensory information received by the brain, that links have been drawn between the network pipelines of these machines and those of the brain. The developing complexities of these network models allow for more useful and powerful applications across many fields.