A Purpose for Nondeterminism: Statistical Inference in the Brain

Nondeterminism isn’t just a quantum byproduct—it serves a critical role in neural computation.

March 25, 2017

In 1927, Werner Heisenberg proposed that the universe is inherently random and, in doing so, he threw the world of physics into a great chaos. Before his time, the standard scientific picture had been one of cause and effect, where the future state of any physical system could be predicted with absolute certainty given the information at hand. In the wake of Heisenberg’s grand pronouncement, however, this deterministic picture was cast aside. Heisenberg and his contemporaries instead developed a new theory that provided unprecedented explanations for experimental results from the early 20th century. Their view, which was soon dubbed “quantum mechanics,” held that the universe was not defined by definite states and outcomes, but rather by a set of probabilities that describe the likelihoods of all possible states and outcomes.

Understandably, nondeterminism has never been an easy pill to swallow. Why, many wonder, would God play dice with the universe? While the answer to that question will perhaps forever remain a mystery, we can state that this arrangement does offer an incredibly powerful resource for computation and learning. The human brain—arguably the most powerful information processing device in existence—makes use of random noise to facilitate highly sophisticated computational functions that would otherwise be infeasible. An important characteristic of cortical neurons is their stochasticity: they produce slightly different, random responses for the same stimulus in consecutive trials. As these neurons develop during nurture, stochasticity helps ensure that the information processing pipeline they construct is robust, ensuring that learned information can be generalized well to novel experiences (in statistics-speak, they avoid over-fitting the training data). In fact, recent literature suggests that the brain’s learning algorithm may be analogous to the powerful statistical learning framework known as “approximate variational inference.” Quickly, an exciting new structure has arisen, one that bridges implementation-level theories of biophysical neural computations and conceptual-level theories of human cognition.

Neural Stochasticity

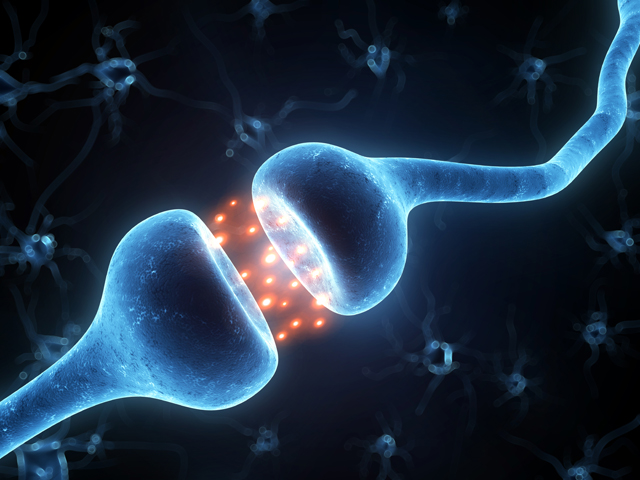

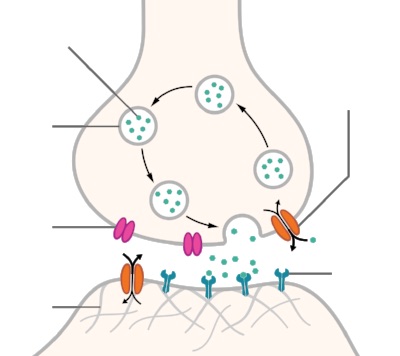

Before one gets to its purpose, it is important to understand the causes of stochasticity in cortical networks. Consider the synapse, the electrochemical junction that enables successive neurons to communicate (diagram below). Electrical signals are passed from one neuron to the next via these junctions, which release chemical messengers known as neurotransmitters to facilitate the transmission. Within the synapse, low-dimensional quantum systems control the release of neurotransmitters. According to quantum theory, the release of these transfer chemicals is inherently random. While it may be possible to control the probability of this chemical release, it is impossible to control with absolute certainty whether the release will occur or not at any given time.

Similar ideas pertain to the triggering of neural spikes. When a neuron receives messages from previous neurons along the pipeline, the magnitude and timing of these messages determines whether it decides to generate a signal that is passed forward in the chain. This decision depends on the electrical potential that exists at the membrane of the current neuron: if this membrane potential rises above a certain threshold, then the neuron fires and a message is passed on. Because the body maintains a temperature above absolute zero, there is non-zero entropy associated with the physical system that surrounds the neural membrane. Entropy is a quantity that describes the amount of randomness in a physical system as governed by the laws of quantum statistical mechanics. Due to this non-zero randomness, the membrane potential is inherently noisy, and neural firing is a stochastic process.

Statistical Inference in the Brain

The seeming unreliability of synaptic connections and neurons described above is not a bug: it is an important feature of neural information processing systems. The inherently stochastic elements of synaptic plasticity enable cortical networks to carry out probabilistic inference by sampling from a variational distribution of network configurations, enabling these networks to learn highly complex representations of the external world that would otherwise be computationally infeasible. Let’s break down what, exactly, that means.

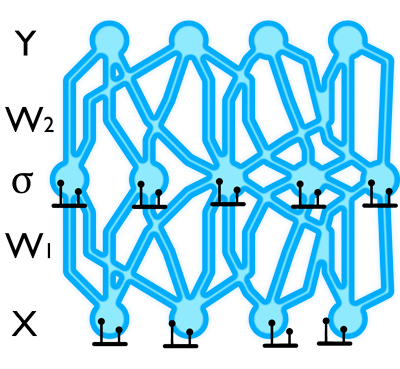

In DeepMind’s Subtle Revolution, I briefly introduced the idea of network connectivity, explaining that it is believed to play an important role in human cognition. Synaptic connections between neurons and the strengths of these connections are thought to encode the long-term memory of an organism, and to determine the capabilities and limitations of various brain functions. The traditional view of synaptic learning assumes that plasticity moves network parameters θ (such as synaptic connections between neurons and the weights of those connections) to values θ* that are optimal for the current computational function of the network. What defines network optimality is a question that is in debate: some argue that the goal is to maximize the amount of information passed from the stimulus to the neural response (efficient coding), while others believe that the optimization task is to find a set of parameters that maximize the likelihood of the observed data under a parameterized probability distribution (maximum likelihood estimation). In each case, the convergence to θ* is assumed to be facilitated by some external regulation of learning rates that reduces the rate as the network approaches an optimal solution.

While the traditional view provides a good starting point for learning theory, there are several issues with this framework. In order for these models to learn effective representations, they need to study a multitude of training examples. A human, however, can reason about the generative structure of the environment from only a few observations. A second issue is that, in the absence of an intelligent external controller, this approach is likely to lead to the internal model over-fitting the sensory experiences; while the resulting model works well for familiar stimuli, it does not generalize well to novel stimuli. Humans, on the other hand, have a remarkable ability to generalize learned experiences to novel stimuli encountered in the environment. Even young children can infer the meaning of a new word, the hidden properties of an object or substance, or the existence of a new causal relation or social rule.

So how is it that humans acquire a commonsense understanding of the world when given, relatively speaking, so little time, data and energy? At a conceptual level, human thought quantitatively embodies “Ockham’s Razor;” that is, we prefer simple explanations of our observations. The basic idea is that simplicity, alongside other criteria such as consistency with the data and coherence with accepted background knowledge, ought to be one of the key criteria for evaluating and choosing between rival theories. This simplicity assumption allows for better generalization of learned information. A human child who is shown photographs of blue jays, lizards and cows can later infer that a cardinal is of the same biological family as the blue jay: she sees that it has wings and feathers, and thus she assumes it to have similar origin as the jay. While this is not the only possible explanation for the data—this bird could very well have been a mammal, like the cow, that developed wings merely to fend off predators—it is the simplest explanation for her observations.

At the implementation level, this new paradigm can be understood as placing a prior probability over the possible parameters θ that may define our internal model of the world. Parameters which are more likely under the simplicity assumption have a higher probability. Rather than learning an optimal set of parameters, θ, the new learning goal is to find an optimal distribution over parameters, p(θ), given the history of observed experiences. This posterior distribution is difficult to evaluate analytically, however; what we have is a distribution over possible internal models of the world, rather than a single model. To effectively approximate this distribution, the brain relies on a variational distribution with a structure that is easy to evaluate. This variational distribution is defined by the various sources of stochasticity within biological neural networks. By iteratively sampling from and updating this variational distribution, the brain moves this distribution as close as possible to the optimal posterior p*(θ). These updates are conducted via biophysical synaptic plasticity mechanisms.

The Neural Basis of Intelligence

Despite significant advances in neuroscience, the neural basis of intelligence remains poorly understood. Here, we have seen a connection between the high-level concept of Ockham’s Razor, borrowed from cognitive science, and the biophysical characteristics of neurons. By merging priors over the space of possible explanations of the world with learned experience, the human mind is able to make robust inferences that go far beyond its own experience. Learning a complex distribution over internal models of the world is a computationally intensive task; stochasticity enables networks of spiking neurons to carry out approximate probabilistic inference through sampling, making this learning task feasible.

The question of whether the brain’s internal model encodes a probability distribution over the states of the external world is heavily contested within the scientific community. Rather than take a side in that debate, I argue that the brain encodes a probability distribution over the internal models themselves; this, I believe, is inherent in its design. Many of the ideas that I have discussed fall under the realm of Bayesian deep learning, a new framework for artificial neural networks that involves uncertainty over model parameters. Bayesian deep learning is a very hot area of research within the artificial intelligence community right now, and I believe that this field has a lot to learn from neuroscience.